An African Spring

“Egypt sees the dam as an existential threat to its

survival, a concern shared, albeit to a s lesser extent, by Sudan. Ethiopia, on

the other hand, regards the dam as vital for its energy needs.” (Chothia,

2020)

Egypt and Ethiopia’s current conflict pertains to the aforementioned

‘water war’ presented in Frey (1993) in which Egypt perceives their goals as

being blocked by Ethiopia and vice versa. The GERD undoubtedly challenges Egypt’s

hegemonic position over the Nile resources and Ethiopia’s decision to build the

GERD without consultation with other riparians may be viewed as a subversive

yet passive revolt against the anachronistic, inequitable and injudicious

allocations of resources by colonial powers. Challenging this power has been

described as ‘an African Spring’ (Tawfik, 2016) pertaining to the uprising of the

Arab spring in late 2010 challenging oppressive regimes, legislations and practices

in the Maghreb. Whether the GERD was an extreme response to the legacies of power

imbalance over the Nile is highly debatable, however, it does beg the question

of whether Ethiopia can meet its need whilst fulling the promises to “transcend

the mistakes of the past [that would]…constrain the present and hinder [unification]

aspirations for the future” (Tawfik, 2018) during the Khartoum framework cooperation

deal on the GERD.

Why did Ethiopia choose to build the dam? The 1929 Anglo-Egyptian

Treaty provisioning the allocation of water rights along the basin was signed

by the United Kingdom, former colonial power, which guaranteed an annual supply

of 48 billion and 4 billion cubic metres to Egypt and Sudan respectively out of

the estimated annual 84 billion cubic metres of Nile water. This was further reallocated

in 1959 which increased Egypt’s share to 55.5 billion cubic meters and Sudan’s

to 17.5 billion (Harb, 2019) with the additional veto power assigned to Egypt. “Nile

Basin Initiative demographic projections for 2050 put Egypt’s and Sudan’s

populations well below those in some of the eight other countries in the

initiative, making the old water agreements appear less fair every day” (Harb,

2019), these agreements set the premise for localised tensions and future conflicts

as the population growth as well as the developmental needs of the riparian

states along the river were insufficiently forecasted or looked over. Decades later,

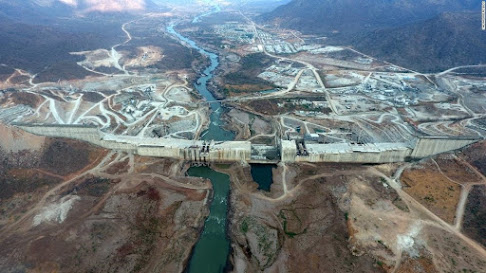

Ethiopia set to build the largest hydroelectric dam in Africa, its ties with China

have become stronger, business and industrial prospects have soared and an

opportunity to lift a significant population out of extreme poverty emerges.

The GERD not only has the opportunity to generate income and tackle poverty by

providing electricity to 66% of the population, expanding the access to clean

water and regulating river flow to maximise production- but completely transform

Ethiopia and place it on level playing field with middle-income countries by 2025.

The installation of the GERD has a host of indirect and inter-generational impacts

on the population of Ethiopia however, the surplus energy provided by the dam

with generation further income from the expansion of industrial sector and the exportation

of energy to neighbouring countries (Woldetatyos, 2020). With so many positives for an individual

riparian along a basin as wide as the Nile it makes the objections against the

stagnation of economic prosperity and poverty reduction particularly difficult

by the international community, thus Egypt’s once passive aggressive stance against

the project is essence is an impending war.

References

Tawfik, R. (2016). “Reconsidering counter-hegemonic dam

projects: the case of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam”. Water Policy,

18(5), pp.1033-1052.

Frey, F., 1993. The Political Context of Conflict and

Cooperation Over International River Basins. Water International,

18(1), pp.54-68.

Chothia, F. (2020). Trump And Africa: How Ethiopia Was

'Betrayed' Over Nile Dam. BBC News. Available at:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-54531747.

Tawfik, R. (2018). Blogpost: Eastern Nile cooperation at a

crossroads: the costs of missing another opportunity. Kujenga Amani.

Harb, I. (2019). River of the Dammed. Blogpost: Foreign

Policy. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/11/15/river-of-the-dammed/.

Woldetatyos, F., 2020. 10 ways the GERD will reduce poverty

in Ethiopia. Blogpost: The Borgen Project, Available at: https://borgenproject.org/ethiopias-gerd/.

i like how you started the blog with a quote, really good introductory paragraph.

ReplyDeleteyou explained the politics of how Ethiopia would benefit from the building of the GERD.

area to improve:

- i think it would be really good if you went more into the politics of the effects of the dam on the lower riparians and how the GERD is fraught with politics due to its effects downstream.